How can God be three persons, yet one God?

The preceding chapters have discussed many attributes of God. But if we understood only those attributes, we would not rightly understand God at all, for we would not understand that God, in his very being, has always existed as more than one person. In fact, God exists as three persons, yet he is one God.

It is important to remember the doctrine of the Trinity in connection with the study of God’s attributes. When we think of God as eternal, omnipresent, omnipotent, and so forth, we may have a tendency to think only of God the Father in connection with these attributes. But the biblical teaching on the Trinity tells us that all of God’s attributes are true of all three persons, for each is fully God. Thus, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit are also eternal, omnipresent, omnipotent, infinitely wise, infinitely holy, infinitely loving, omniscient, and so forth

The doctrine of the Trinity is one of the most important doctrines of the Christian faith. To study the Bible’s teachings on the Trinity gives us great insight into the question that is at the center of all of our seeking after God: What is God like in himself? Here we learn that in himself, in his very being, God exists in the persons of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, yet he is one God.

EXPLANATION AND SCRIPTURAL BASIS

We may define the doctrine of the Trinity as follows: God eternally exists as three persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and each person is fully God, and there is one God.

A. The Doctrine of the Trinity Is Progressively Revealed in Scripture

1. Partial Revelation in the Old Testament. The word trinity is never found in the Bible, though the idea represented by the word is taught in many places. The word trinity means “tri-unity” or “three-in-oneness.” It is used to summarize the teaching of Scripture that God is three persons yet one God.

Sometimes people think the doctrine of the Trinity is found only in the New Testament, not in the Old. If God has eternally existed as three persons, it would be surprising to find no indications of that in the Old Testament. Although the doctrine of the Trinity is not explicitly found in the Old Testament, several passages suggest or even imply that God exists as more than one person.

For instance, according to Genesis 1:26, God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.” What do the plural verb (“let us”) and the plural pronoun (“our”) mean? Some have suggested they are plurals of majesty, a form of speech a king would use in saying, for example, “We are pleased to grant your request.”1 However, in Old Testament Hebrew there are no other examples of a monarch using plural verbs or plural pronouns of himself in such a “plural of majesty,” so this suggestion has no evidence to support it.2 Another suggestion is that God is here speaking to angels. But angels did not participate in the creation of man, nor was man created in the image and likeness of angels, so this suggestion is not convincing. The best explanation is that already in the first chapter of Genesis we have an indication of a plurality of persons in God himself.3 We are not told how many persons, and we have nothing approaching a complete doctrine of the Trinity, but it is implied that more than one person is involved. The same can be said of Genesis 3:22 (“Behold, the man has become like one of us knowing good and evil”), Genesis 11:7 (“Come, let us go down, and there confuse their language”), and Isaiah 6:8 (“Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?”). (Note the combination of singular and plural in the same sentence in the last passage.

Moreover, there are passages where one person is called “God” or “the Lord” and is distinguished from another person who is also said to be God. In Psalm 45:6–7 (NIV), the psalmist says, “Your throne, O God, will last for ever and ever … You love righteousness and hate wickedness; therefore God, your God, has set you above your companions by anointing you with the oil of joy.” Here the psalm passes beyond describing anything that could be true of an earthly king and calls the king “God” (v. 6), whose throne will last “forever and ever.” But then, still speaking to the person called “God,” the author says that “God, your God, has set you above your companions” (v. 7). So two separate persons are called “God” (Heb. אֱלֹהִים, H466). In the New Testament, the author of Hebrews quotes this passage and applies it to Christ: “Your throne, O God, is for ever and ever” (Heb. 1:8).4

Similarly, in Psalm 110:1, David says, “The LORD says to my lord: “Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet” ’ (NIV). Jesus rightly understands that David is referring to two separate persons as “Lord” (Matt. 22:41–46), but who is David’s “Lord” if not God himself? And who could be saying to God, “Sit at my right hand” except someone else who is also fully God? From a New Testament perspective, we can paraphrase this verse: “God the Father said to God the Son, “Sit at my right hand.” ’ But even without the New Testament teaching on the Trinity, it seems clear that David was aware of a plurality of persons in one God. Jesus, of course, understood this, but when he asked the Pharisees for an explanation of this passage, “no one was able to answer him a word, nor from that day did any one dare to ask him any more questions” (Matt. 22:46). Unless they are willing to admit a plurality of persons in one God, Jewish interpreters of Scripture to this day will have no more satisfactory explanation of Psalm 110:1 (or of Gen. 1:26, or of the other passages just discussed) than they did in Jesus day

Isaiah 63:10 says that God’s people “rebelled and grieved his Holy Spirit” (NIV), apparently suggesting both that the Holy Spirit is distinct from God himself (it is “his Holy Spirit”), and that this Holy Spirit can be “grieved,” thus suggesting emotional capabilities characteristic of a distinct person. (Isa. 61:1 also distinguishes “The Spirit of the Lord GOD” from “the LORD,” even though no personal qualities are attributed to the Spirit of the Lord in that verse.)

Similar evidence is found in Malachi, when the Lord says, “The Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple; the messenger of the covenant in whom you delight, behold, he is coming, says the LORD of hosts. But who can endure the day of his coming, and who can stand when he appears?” (Mal. 3:1–2). Here again the one speaking (“the LORD of hosts”) distinguishes himself from “the Lord whom you seek,” suggesting two separate persons, both of whom can be called “Lord.”

In Hosea 1:7, the Lord is speaking, and says of the house of Judah, “I will deliver them by the LORD their God,” once again suggesting that more than one person can be called “Lord” (Heb. יהוה, H3378) and “God” (אֱלֹהִים, H466).

And in Isaiah 48:16, the speaker (apparently the servant of the Lord) says, “And now the Lord God has sent me and his Spirit.”5 Here the Spirit of the Lord, like the servant of the Lord, has been “sent” by the Lord GOD on a particular mission. The parallel between the two objects of sending (“me” and “his Spirit”) would be consistent with seeing them both as distinct persons: it seems to mean more than simply “the Lord has sent me and his power.”6 In fact, from a full New Testament perspective (which recognizes Jesus the Messiah to be the true servant of the Lord predicted in Isaiah’s prophecies), Isaiah 48:16 has trinitarian implications: “And now the Lord God has sent me and his Spirit,” if spoken by Jesus the Son of God, refers to all three persons of the Trinity

Furthermore, several Old Testament passages about “the angel of the LORD” suggest a plurality of persons in God. The word translated “angel” (Heb. מַלְאָךְ, H4855) means simply “messenger.” If this angel of the LORD is a “messenger” of the LORD, he is then distinct from the LORD himself. Yet at some points the angel of the LORD is called “God” or “the LORD” (see Gen. 16:13; Ex. 3:2–6; 23:20–22 [note “my name is in him” in v. 21]; Num. 22:35 with 38; Judg. 2:1–2; 6:11 with 14). At other points in the Old Testament “the angel of the LORD” simply refers to a created angel, but at least at these texts the special angel (or “messenger”) of the LORD seems to be a distinct person who is fully divine

One of the most disputed Old Testament texts that could show distinct personality for more than one person is Proverbs 8:22–31. Although the earlier part of the chapter could be understood as merely a personification of “wisdom” for literary effect, showing wisdom calling to the simple and inviting them to learn, vv. 22–31, one could argue, say things about “wisdom” that seem to go far beyond mere personification. Speaking of the time when God created the earth, “wisdom” says, “Then I was the craftsman at his side. I was filled with delight day after day, rejoicing always in his presence, rejoicing in his whole world and delighting in mankind” (Prov. 8:30–31 NIV). To work as a “craftsman” at God’s side in the creation suggests in itself the idea of distinct personhood, and the following phrases might seem even more convincing, for only real persons can be “filled with delight day after day” and can rejoice in the world and delight in mankind.7

But if we decide that “wisdom” here really refers to the Son of God before he became man, there is a difficulty. Verses 22–25 (RSV) seem to speak of the creation of this person who is called “wisdom”:

The LORD created me at the beginning of his work,

The first of his acts of old.

Ages ago I was set up,

at the first, before the beginning of the earth.

When there were no depths I was brought forth,

when there were no springs abounding with water.

Before the mountains had been shaped,

before the hills, I was brought forth.

Does this not indicate that this “wisdom” was created?

In fact, it does not. The Hebrew word that commonly means “create” (בָּרָא, H1343) is not used in verse 22; rather the word is קָנָה, H7865, which occurs eighty-four times in the Old Testament and almost always means “to get, acquire.” The NASB is most clear here: “The Lord possessed me at the beginning of his way” (similarly KJV). (Note this sense of the word in Gen. 39:1; Ex. 21:2; Prov. 4:5, 7; 23:23; Eccl. 2:7; Isa. 1:3 [“owner”].) This is a legitimate sense and, if wisdom is understood as a real person, would mean only that God the Father began to direct and make use of the powerful creative work of God the Son at the time creation began8: the Father summoned the Son to work with him in the activity of creation. The expression “brought forth” in verses 24 and 25 is a different term but could carry a similar meaning: the Father began to direct and make use of the powerful creative work of the Son in the creation of the universe.

2. More Complete Revelation of the Trinity in the New Testament. When the New Testament opens, we enter into the history of the coming of the Son of God to earth. It is to be expected that this great event would be accompanied by more explicit teaching about the trinitarian nature of God, and that is in fact what we find. Before looking at this in detail, we can simply list several passages where all three persons of the Trinity are named together.

When Jesus was baptized, “the heavens were opened and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and alighting on him; and lo, a voice from heaven, saying, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased” ’ (Matt. 3:16–17). Here at one moment we have three members of the Trinity performing three distinct activities. God the Father is speaking from heaven; God the Son is being baptized and is then spoken to from heaven by God the Father; and God the Holy Spirit is descending from heaven to rest upon and empower Jesus for his ministry.

At the end of Jesus’ earthly ministry, he tells the disciples that they should go “and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matt. 28:19). The very names “Father” and “Son,” drawn as they are from the family, the most familiar of human institutions, indicate very strongly the distinct personhood of both the Father and the Son. When “the Holy Spirit” is put in the same expression and on the same level as the other two persons, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the Holy Spirit is also viewed as a person and of equal standing with the Father and the Son

When we realize that the New Testament authors generally use the name “God” (Gk. θεός, G2536) to refer to God the Father and the name “Lord” (Gk. Κύριος, G3261) to refer to God the Son, then it is clear that there is another trinitarian expression in 1 Corinthians 12:4–6: “Now there are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit; and there are varieties of service, but the same Lord; and there are varieties of working, but it is the same God who inspires them all in every one.”

Similarly, the last verse of 2 Corinthians is trinitarian in its expression: “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all” (2 Cor. 13:14). We see the three persons mentioned separately in Ephesians 4:4–6 as well: “There is one body and one Spirit just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call, one Lord one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all, who is above all and through all and in all.”

All three persons of the Trinity are mentioned together in the opening sentence of 1 Peter: “According to the foreknowledge of God the Father, by the sanctifying work of the Spirit, that you may obey Jesus Christ and be sprinkled with his blood” (1 Peter 1:2 NASB). And in Jude 20–21, we read: “But you, beloved, build yourselves up on your most holy faith; pray in the Holy Spirit; keep yourselves in the love of God; wait for the mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ unto eternal life.

However, the KJV translation of 1 John 5:7 should not be used in this connection. It reads, “For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.”

The problem with this translation is that it is based on a very small number of unreliable Greek manuscripts, the earliest of which comes from the fourteenth century A.D. No modern translation (except NKJV) includes this KJV reading, but all omit it, as do the vast majority of Greek manuscripts from all major text traditions, including several very reliable manuscripts from the fourth and fifth century A.D., and also including quotations by church fathers such as Irenaeus (d. ca. A.D. 202), Clement of Alexandria (d. ca. A.D. 212), Tertullian (died after A.D. 220), and the great defender of the Trinity, Athanasius (d. A.D. 373).

B. Three Statements Summarize the Biblical Teaching

In one sense the doctrine of the Trinity is a mystery that we will never be able to understand fully. However, we can understand something of its truth by summarizing the teaching of Scripture in three statements:

1. God is three persons.

2. Each person is fully God.

3. There is one God.

The following section will develop each of these statements in more detail.

1. God Is Three Persons. The fact that God is three persons means that the Father is not the Son; they are distinct persons. It also means that the Father is not the Holy Spirit, but that they are distinct persons. And it means that the Son is not the Holy Spirit. These distinctions are seen in a number of the passages quoted in the earlier section as well as in many additional New Testament passages.

John 1:1–2 tells us: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God.” The fact that the “Word” (who is seen to be Christ in vv. 9–18) is “with” God shows distinction from God the Father. In John 17:24 (NIV), Jesus speaks to God the Father about “my glory, the glory you have given me because you loved me before the creation of the world,” thus showing distinction of persons, sharing of glory, and a relationship of love between the Father and the Son before the world was created

We are told that Jesus continues as our High Priest and Advocate before God the Father: “If any one does sin, we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous” (1 John 2:1). Christ is the one who “is able for all time to save those who draw near to God through him, since he always lives to make intercession for them” (Heb. 7:25). Yet in order to intercede for us before God the Father, it is necessary that Christ be a person distinct from the Father.

Moreover, the Father is not the Holy Spirit, and the Son is not the Holy Spirit. They are distinguished in several verses. Jesus says, “But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you” (John 14:26). The Holy Spirit also prays or “intercedes” for us (Rom. 8:27), indicating a distinction between the Holy Spirit and God the Father to whom the intercession is made.

Finally, the fact that the Son is not the Holy Spirit is also indicated in the several trinitarian passages mentioned earlier, such as the Great Commission (Matt. 28:19), and in passages that indicate that Christ went back to heaven and then sent the Holy Spirit to the church. Jesus said, “It is to your advantage that I go away, for if I do not go away, the Counselor will not come to you; but if I go, I will send him to you” (John 16:7).

Some have questioned whether the Holy Spirit is indeed a distinct person, rather than just the “power” or “force” of God at work in the world. But the New Testament evidence is quite clear and strong.9 First are the several verses mentioned earlier where the Holy Spirit is put in a coordinate relationship with the Father and the Son (Matt. 28:19; 1 Cor. 12:4–6; 2 Cor. 13:14; Eph. 4:4–6; 1 Peter 1:2): since the Father and Son are both persons, the coordinate expression strongly intimates that the Holy Spirit is a person also. Then there are places where the masculine pronoun ἥ (Gk. ἐκεῖνος, G1697) is applied to the Holy Spirit (John 14:26; 15:26; 16:13–14), which one would not expect from the rules of Greek grammar, for the word “spirit” (Gk. πνεῦμα, G4460) is neuter, not masculine, and would ordinarily be referred to with the neuter pronoun ἐκεῖνο. Moreover, the name counselor or comforter (Gk. παράκλητος, G4156) is a term commonly used to speak of a person who helps or gives comfort or counsel to another person or persons, but is used of the Holy Spirit in John’s gospel (14:16, 26; 15:26; 16:7)

Other personal activities are ascribed to the Holy Spirit, such as teaching (John 14:26), bearing witness (John 15:26; Rom. 8:16), interceding or praying on behalf of others (Rom. 8:26–27), searching the depths of God (1 Cor. 2:10), knowing the thoughts of God (1 Cor. 2:11), willing to distribute some gifts to some and other gifts to others (1 Cor. 12:11), forbidding or not allowing certain activities (Acts 16:6–7), speaking (Acts 8:29; 13:2; and many times in both Old and New Testaments), evaluating and approving a wise course of action (Acts 15:28), and being grieved by sin in the lives of Christians (Eph. 4:30).

Finally, if the Holy Spirit is understood simply to be the power of God, rather than a distinct person, then a number of passages would simply not make sense, because in them the Holy Spirit and his power or the power of God are both mentioned. For example, Luke 4:14, “And Jesus returned in the power of the Spirit into Galilee,” would have to mean, “Jesus returned in the power of the power of God into Galilee.” In Acts 10:38, “God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and with power,” would mean, “God anointed Jesus with the power of God and with power” (see also Rom. 15:13; 1 Cor. 2:4)

Although so many passages clearly distinguish the Holy Spirit from the other members of the Trinity, one puzzling verse has been 2 Corinthians 3:17: “Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.” Interpreters often assume that “the Lord” here must mean Christ, because Paul frequently uses “the Lord” to refer to Christ. But that is probably not the case here, for a good argument can be made from grammar and context to say that this verse is better translated with the Holy Spirit as subject, “Now the Spirit is the Lord …”10 In this case, Paul would be saying that the Holy Spirit is also “Yahweh” (or “Jehovah”), the Lord of the Old Testament (note the clear Old Testament background of this context, beginning at v. 7). Theologically this would be quite acceptable, for it could truly be said that just as God the Father is “Lord” and God the Son is “Lord” (in the full Old Testament sense of “Lord” as a name for God), so also the Holy Spirit is the one called “Lord” in the Old Testament—and it is the Holy Spirit who especially manifests the presence of the Lord to us in the new covenant age.11

2. Each Person Is Fully God. In addition to the fact that all three persons are distinct, the abundant testimony of Scripture is that each person is fully God as well.

First, God the Father is clearly God. This is evident from the first verse of the Bible, where God created the heaven and the earth. It is evident through the Old and New Testaments, where God the Father is clearly viewed as sovereign Lord over all and where Jesus prays to his Father in heaven.

Next, the Son is fully God. Although this point will be developed in greater detail in chapter 26, “The Person of Christ,” we can briefly note several explicit passages at this point. John 1:1–4 clearly affirms the full deity of Christ:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men.

Here Christ is referred to as “the Word,” and John says both that he was “with God” and that he “was God.” The Greek text echoes the opening words of Genesis 1:1 (“In the beginning …”) and reminds us that John is talking about something that was true before the world was made. God the Son was always fully God

The translation “the Word was God” has been challenged by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who translate it “the Word was a god “implying that the Word was simply a heavenly being but not fully divine. They justify this translation by pointing to the fact that the definite article (Gk. ὁ, G3836, “the”) does not occur before the Greek word θεός (G2536, “God”). They say therefore that θεός should be translated “a god.” However, their interpretation has been followed by no recognized Greek scholar anywhere, for it is commonly known that the sentence follows a regular rule of Greek grammar, and the absence of the definite article merely indicates that “God” is the predicate rather than the subject of the sentence.12 (A recent publication by the Jehovah’s Witnesses now acknowledges the relevant grammatical rule but continues to affirm their position on John 1:1 nonetheless.)13

The inconsistency of the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ position can further be seen in their translation of the rest of the chapter. For various other grammatical reasons the word θεός (G2536) also lacks the definite article at other places in this chapter, such as verse 6 (“There was a man sent from God”), verse 12 (“power to become children of God”), verse 13 (“but of God”), and verse 18 (“No one has ever seen God”). If the Jehovah’s Witnesses were consistent with their argument about the absence of the definite article, they would have to translate all of these with the phrase “a god,” but they translate “God” in every case

John 20:28 in its context is also a strong proof for the deity of Christ. Thomas had doubted the reports of the other disciples that they had seen Jesus raised from the dead, and he said he would not believe unless he could see the nail prints in Jesus’ hands and place his hand in his wounded side (John 20:25). Then Jesus appeared to the disciples when Thomas was with them. He said to Thomas, “Put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side; do not be faithless, but believing” (John 20:27). In response to this, we read, “Thomas answered him, “My Lord and my God!” ’ (John 20:28). Here Thomas calls Jesus “my God.” The narrative shows that both John in writing his gospel and Jesus himself approve of what Thomas has said and encourage everyone who hears about Thomas to believe the same things that Thomas did. Jesus immediately responds to Thomas, “Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe” (John 20:29). As far as John is concerned, this is the dramatic high point of the gospel, for he immediately tells the reader—in the very next verse—that this was the reason he wrote it:

Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book; but these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name. (John 20:30–31)

Jesus speaks of those who will not see him and will yet believe, and John immediately tells the reader that he recorded the events written in his gospel in order that they may believe in just this way, imitating Thomas in his confession of faith. In other words, the entire gospel is written to persuade people to imitate Thomas, who sincerely called Jesus “My Lord and my God.” Because this is set out by John as the purpose of his gospel, the sentence takes on added force.14

Other passages speaking of Jesus as fully divine include Hebrews 1, where the author says that Christ is the “exact representation” (vs. 3, Gk. χαρακτήρ, G5917, “exact duplicate”) of the nature or being (Gk. ὑπόστασις, G5712) of God—meaning that God the Son exactly duplicates the being or nature of God the Father in every way: whatever attributes or power God the Father has, God the Son has them as well. The author goes on to refer to the Son as “God” in verse 8 (“But of the Son he says, “Your throne, O God, is for ever and ever” ’), and he attributes the creation of the heavens to Christ when he says of him, “You, Lord, did found the earth in the beginning, and the heavens are the work of your hands” (Heb. 1:10, quoting Ps. 102:25). Titus 2:13 refers to “our great God and Savior Jesus Christ,” and 2 Peter 1:1 speaks of “the righteousness of our God and Savior Jesus Christ.”15 Romans 9:5, speaking of the Jewish people, says, “Theirs are the patriarchs, and from them is traced the human ancestry of Christ, who is God over all, forever praised! Amen” (NIV).16

In the Old Testament, Isaiah 9:6 predicts,

“For to us a child is born,

to us a son is given;

and the government will be upon his shoulder,

and his name will be called

‘Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God.’ ”

As this prophecy is applied to Christ, it refers to him as “Mighty God.” Note the similar application of the titles “LORD” and “God” in the prophecy of the coming of the Messiah in Isaiah 40:3, “In the wilderness prepare the way of the LORD, make straight in the desert a highway for our God,” quoted by John the Baptist in preparation for the coming of Christ in Matthew 3:3.

Many other passages will be discussed in chapter 26 below, but these should be sufficient to demonstrate that the New Testament clearly refers to Christ as fully God. As Paul says in Colossians 2:9, “In him the whole fulness of deity dwells bodily.

Next, the Holy Spirit is also fully God. Once we understand God the Father and God the Son to be fully God, then the trinitarian expressions in verses like Matthew 28:19 (“baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit”) assume significance for the doctrine of the Holy Spirit, because they show that the Holy Spirit is classified on an equal level with the Father and the Son. This can be seen if we recognize how unthinkable it would have been for Jesus to say something like, “baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the archangel Michael—this would give to a created being a status entirely inappropriate even to an archangel. Believers throughout all ages can only be baptized into the name (and thus into a taking on of the character) of God himself.17 (Note also the other trinitarian passages mentioned above: 1 Cor. 12:4–6; 2 Cor. 13:14; Eph. 4:4–6; 1 Peter 1:2; Jude 20–21.

In Acts 5:3–4, Peter asks Ananias, “Why has Satan filled your heart to lie to the Holy Spirit …? You have not lied to men but to God.” According to Peter’s words, to lie to the Holy Spirit is to lie to God. Paul says in 1 Corinthians 3:16, “Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?” God’s temple is the place where God himself dwells, which Paul explains by the fact that “God’s Spirit” dwells in it, thus apparently equating God’s Spirit with God himself.

David asks in Psalm 139:7–8, “Whither shall I go from your Spirit? Or whither shall I flee from your presence? If I ascend to heaven, you are there!” This passage attributes the divine characteristic of omnipresence to the Holy Spirit, something that is not true of any of God’s creatures. It seems that David is equating God’s Spirit with God’s presence. To go from God’s Spirit is to go from his presence, but if there is nowhere that David can flee from God’s Spirit, then he knows that wherever he goes he will have to say, “You are there.

Paul attributes the divine characteristic of omniscience to the Holy Spirit in 1 Corinthians 2:10–11: “For the Spirit searches everything, even the depths of God. For what person knows a man’s thoughts except the spirit of the man which is in him? So also no one comprehends the thoughts of God [Gk., literally “the things of God’] except the Spirit of God.”

Moreover, the activity of giving new birth to everyone who is born again is the work of the Holy Spirit. Jesus said, “unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God. That which is born of the flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit. Do not marvel that I said to you, “You must be born anew” ’ (John 3:5–7). But the work of giving new spiritual life to people when they become Christians is something that only God can do (cf. 1 John 3:9, “born of God”). This passage therefore gives another indication that the Holy Spirit is fully God.

Up to this point we have two conclusions, both abundantly taught throughout Scripture:

1. God is three persons.

2. Each person is fully God.

If the Bible taught only these two facts, there would be no logical problem at all in fitting them together, for the obvious solution would be that there are three Gods. The Father is fully God, the Son is fully God, and the Holy Spirit is fully God. We would have a system where there are three equally divine beings. Such a system of belief would be called polytheism—or, more specifically, “tritheism,” or belief in three Gods. But that is far from what the Bible teaches.

3. There Is One God. Scripture is abundantly clear that there is one and only one God. The three different persons of the Trinity are one not only in purpose and in agreement on what they think, but they are one in essence, one in their essential nature. In other words, God is only one being. There are not three Gods. There is only one God.

One of the most familiar passages of the Old Testament is Deuteronomy 6:4–5 (NIV): “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one. Love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength.”

When Moses sings,

“Who is like you, O LORD, among the gods?

Who is like you, majestic in holiness,

terrible in glorious deeds, doing wonders?” (Ex. 15:11)

the answer obviously is “No one.” God is unique, and there is no one like him and there can be no one like him. In fact, Solomon prays “that all the peoples of the earth may know that the LORD is God; there is no other” (1 Kings 8:60).

When God speaks, he repeatedly makes it clear that he is the only true God; the idea that there are three Gods to be worshiped rather than one would be unthinkable in the light of these extremely strong statements. God alone is the one true God and there is no one like him. When he speaks, he alone is speaking—he is not speaking as one God among three who are to be worshiped. He says:

“I am the LORD, and there is no other,

besides me there is no God;

I gird you, though you do not know me,

that men may know, from the rising of the sun

and from the west, that there is none besides me;

I am the LORD, and there is no other.” (Isa. 45:5–6)

Similarly, he calls everyone on earth to turn to him:

There is no other god besides me,

a righteous God and a Savior;

there is none besides me.

“Turn to me and be saved,

all the ends of the earth!

For I am God, and there is no other.”

(Isa. 45:21–22; cf. 44:6–8)

The New Testament also affirms that there is one God. Paul writes, “For there is one God and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (1 Tim. 2:5). Paul affirms that “God is one” (Rom. 3:30), and that “there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist” (1 Cor. 8:6).18 Finally, James acknowledges that even demons recognize that there is one God, even though their intellectual assent to that fact is not enough to save them: “You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe—and shudder” (James 2:19). But clearly James affirms that one “does well” to believe that “God is one.”

4. Simplistic Solutions Must All Deny One Strand of Biblical Teaching. We now have three statements, all of which are taught in Scripture:

1. God is three persons.

2. Each person is fully God.

3. There is one God.

Throughout the history of the church there have been attempts to come up with a simple solution to the doctrine of the Trinity by denying one or another of these statements. If someone denies the first statement then we are simply left with the fact that each of the persons named in Scripture (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) is God, and there is one God. But if we do not have to say that they are distinct persons, then there is an easy solution: these are just different names for one person who acts differently at different times. Sometimes this person calls himself Father, sometimes he calls himself Son, and sometimes he calls himself Spirit.19 We have no difficulty in understanding that, for in our own experience the same person can act at one time as a lawyer (for example), at another time as a father to his own children, and at another time as a son with respect to his parents: The same person is a lawyer, a father, and a son. But such a solution would deny the fact that the three persons are distinct individuals, that God the Father sends God the Son into the world, that the Son prays to the Father, and that the Holy Spirit intercedes before the Father for us.

Another simple solution might be found by denying the second statement that is, denying that some of the persons named in Scripture are really fully God. If we simply hold that God is three persons, and that there is one God, then we might be tempted to say that some of the “persons” in this one God are not fully God, but are only subordinate or created parts of God. This solution would be taken, for example, by those who deny the full deity of the Son (and of the Holy Spirit).20 But, as we saw above, this solution would have to deny an entire category of biblical teaching.

Finally, as we noted above, a simple solution could come by denying that there is one God. But this would result in a belief in three Gods, something clearly contrary to Scripture.

Though the third error has not been common, as we shall see below, each of the first two errors has appeared at one time or another in the history of the church and they still persist today in some groups.

5. All Analogies Have Shortcomings. If we cannot adopt any of these simple solutions, then how can we put the three truths of Scripture together and maintain the doctrine of the Trinity? Sometimes people have used several analogies drawn from nature or human experience to attempt to explain this doctrine. Although these analogies are helpful at an elementary level of understanding, they all turn out to be inadequate or misleading on further reflection. To say, for example, that God is like a three-leaf clover, which has three parts yet remains one clover, fails because each leaf is only part of the clover, and any one leaf cannot be said to be the whole clover. But in the Trinity, each of the persons is not just a separate part of God, each person is fully God. Moreover, the leaf of a clover is impersonal and does not have distinct and complex personality in the way each person of the Trinity does

Others have used the analogy of a tree with three parts: the roots, trunk, and branches all constitute one tree. But a similar problem arises, for these are only parts of a tree, and none of the parts can be said to be the whole tree. Moreover, in this analogy the parts have different properties, unlike the persons of the Trinity, all of whom possess all of the attributes of God in equal measure. And the lack of personality in each part is a deficiency as well.

The analogy of the three forms of water (steam, water, and ice) is also inadequate because (a) no quantity of water is ever all three of these at the same time,21 (b) they have different properties or characteristics, (c) the analogy has nothing that corresponds to the fact that there is only one God (there is no such thing as “one water” or “all the water in the universe”), and (d) the element of intelligent personality is lacking.

Other analogies have been drawn from human experience. It might be said that the Trinity is something like a man who is both a farmer, the mayor of his town, and an elder in his church. He functions in different roles at different times, but he is one man. However, this analogy is very deficient because there is only one person doing these three activities at different times, and the analogy cannot deal with the personal interaction among the members of the Trinity. (In fact, this analogy simply teaches the heresy called modalism, discussed below.

Another analogy taken from human life is the union of the intellect, the emotions, and the will in one human person. While these are parts of a personality, however, no one factor constitutes the entire person. And the parts are not identical in characteristics but have different abilities

So what analogy shall we use to teach the Trinity? Although the Bible uses many analogies from nature and life to teach us various aspects of God’s character (God is like a rock in his faithfulness, he is like a shepherd in his care, etc.), it is interesting that Scripture nowhere uses any analogies to teach the doctrine of the Trinity. The closest we come to an analogy is found in the titles “Father” and “Son” themselves, titles that clearly speak of distinct persons and of the close relationship that exists between them in a human family. But on the human level, of course, we have two entirely separate human beings, not one being comprised of three distinct persons. It is best to conclude that no analogy adequately teaches about the Trinity, and all are misleading in significant ways.

6. God Eternally and Necessarily Exists as the Trinity. When the universe was created God the Father spoke the powerful creative words that brought it into being, God the Son was the divine agent who carried out these words (John 1:3; 1 Cor. 8:6; Col. 1:16; Heb. 1:2), and God the Holy Spirit was active “moving over the face of the waters” (Gen. 1:2). So it is as we would expect: if all three members of the Trinity are equally and fully divine, then they have all three existed for all eternity, and God has eternally existed as a Trinity (cf. also John 17:5, 24). Moreover, God cannot be other than he is, for he is unchanging (see chapter 11 above). Therefore it seems right to conclude that God necessarily exists as a Trinity—he cannot be other than he is.

C. Errors Have Come By Denying Any of the Three Statements Summarizing the Biblical Teaching

In the previous section we saw how the Bible requires that we affirm the following three statements:

1. God is three persons.

2. Each person is fully God.

3. There is one God.

Before we discuss further the differences between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and the way they relate to one another, it is important that we recall some of the doctrinal errors about the Trinity that have been made in the history of the church. In this historical survey we will see some of the mistakes that we ourselves should avoid in any further thinking about this doctrine. In fact, the major trinitarian errors that have arisen have come through a denial of one or another of these three primary statements.22

1. Modalism Claims That There Is One Person Who Appears to Us in Three Different Forms (or “Modes”). At various times people have taught that God is not really three distinct persons, but only one person who appears to people in different “modes” at different times. For example, in the Old Testament God appeared as “Father.” Throughout the Gospels, this same divine person appeared as “the Son” as seen in the human life and ministry of Jesus. After Pentecost, this same person then revealed himself as the “Spirit” active in the church.

This teaching is also referred to by two other names. Sometimes it is called Sabellianism, after a teacher named Sabellius who lived in Rome in the early third century A.D. Another term for modalism is “modalistic monarchianism,” because this teaching not only says that God revealed himself in different “modes” but it also says that there is only one supreme ruler (“monarch”) in the universe and that is God himself, who consists of only one person.

Modalism gains its attractiveness from the desire to emphasize clearly the fact that there is only one God. It may claim support not only from the passages talking about one God, but also from passages such as John 10:30 (“I and the Father are one”) and John 14:9 (“He who has seen me has seen the Father”). However, the last passage can simply mean that Jesus fully reveals the character of God the Father, and the former passage (John 10:30), in a context in which Jesus affirms that he will accomplish all that the Father has given him to do and save all whom the Father has given to him, seems to mean that Jesus and the Father are one in purpose (though it may also imply oneness of essence).

The fatal shortcoming of modalism is the fact that it must deny the personal relationships within the Trinity that appear in so many places in Scripture (or it must affirm that these were simply an illusion and not real). Thus, it must deny three separate persons at the baptism of Jesus, where the Father speaks from heaven and the Spirit descends on Jesus like a dove. And it must say that all those instances where Jesus is praying to the Father are an illusion or a charade. The idea of the Son or the Holy Spirit interceding for us before God the Father is lost. Finally, modalism ultimately loses the heart of the doctrine of the atonement—that is, the idea that God sent his Son as a substitutionary sacrifice, and that the Son bore the wrath of God in our place, and that the Father, representing the interests of the Trinity, saw the suffering of Christ and was satisfied (Isa. 53:11)

Moreover, modalism denies the independence of God, for if God is only one person, then he has no ability to love and to communicate without other persons in his creation. Therefore it was necessary for God to create the world, and God would no longer be independent of creation (see chapter 12, above, on God’s independence).

One present denomination within Protestantism (broadly defined), the United Pentecostal Church, is modalistic in its doctrinal position.23

2. Arianism Denies the Full Deity of the Son and the Holy Spirit.

a. The Arian Controversy: The term Arianism is derived from Arius, a Bishop of Alexandria whose views were condemned at the Council of Nicea in A.D. 325, and who died in A.D. 336. Arius taught that God the Son was at one point created by God the Father, and that before that time the Son did not exist, nor did the Holy Spirit, but the Father only. Thus, though the Son is a heavenly being who existed before the rest of creation and who is far greater than all the rest of creation, he is still not equal to the Father in all his attributes—he may even be said to be “like the Father” or “similar to the Father” in his nature, but he cannot be said to be “of the same nature” as the Father

The Arians depended heavily on texts that called Christ God’s “only begotten” Son (John 1:14; 3:16, 18; 1 John 4:9). If Christ were “begotten” by God the Father, they reasoned, it must mean that he was brought into existence by God the Father (for the word “beget” in human experience refers to the father’s role in conceiving a child). Further support for the Arian view was found in Colossians 1:15, “He is the image of the invisible God, the first-born of all creation.” Does not “first-born” here imply that the Son was at some point brought into existence by the Father?24 And if this is true of the Son, it must necessarily be true of the Holy Spirit as well

But these texts do not require us to believe the Arian position. Colossians 1:15, which calls Christ “the first-born of all creation,” is better understood to mean that Christ has the rights or privileges of the “first-born—that is, according to biblical usage and custom, the right of leadership or authority in the family for one’s generation. (Note Heb. 12:16 where Esau is said to have sold his “first-born status” or “birthright—the Greek word πρωτοτόκια, G4757, is cognate to the term πρωτότοκος, G4758, “first-born” in Col. 1:15.) So Colossians 1:15 means that Christ has the privileges of authority and rule, the privileges belonging to the “first-born,” but with respect to the whole creation. The NIV translates it helpfully, “the firstborn over all creation.

As for the texts that say that Christ was God’s “only begotten Son,” the early church felt so strongly the force of many other texts showing that Christ was fully and completely God, that it concluded that, whatever “only begotten” meant, it did not mean “created.” Therefore the Nicene Creed in 325 affirmed that Christ was “begotten, not made”:

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father, the only-begotten; that is, of the essence of the Father, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance (ὁμοούσιον) with the Father …25

This same phrase was reaffirmed at the Council of Constantinople in 381. In addition, the phrase “before all ages” was added after “begotten of the Father,” to show that this “begetting” was eternal. It never began to happen, but is something that has been eternally true of the relationship between the Father and the Son. However, the nature of that “begetting” has never been defined very clearly, other than to say that it has to do with the relationship between the Father and the Son, and that in some sense the Father has eternally had a primacy in that relationship

In further repudiation of the teaching of Arius, the Nicene Creed insisted that Christ was “of the same substance as the Father.” The dispute with Arius concerned two words that have become famous in the history of Christian doctrine, ὁμοούσιος (“of the same nature”) and ὁμοιούσιος (“of a similar nature”).26 The difference depends on the different meaning of two Greek prefixes, ὁμο—meaning “same,” and ὁμοι—meaning “similar.” Arius was happy to say that Christ was a supernatural heavenly being and that he was created by God before the creation of the rest of the universe, and even that he was “similar” to God in his nature. Thus, Arius would agree to the word ὁμοιούσιος. But the Council of Nicea in 325 and the Council of Constantinople in 381 realized that this did not go far enough, for if Christ is not of exactly the same nature as the Father, then he is not fully God. So both councils insisted that orthodox Christians confess Jesus to be ὁμοούσιος of the same nature as God the Father. The difference between the two words was only one letter, the Greek letter iota, and some have criticized the church for allowing a doctrinal dispute over a single letter to consume so much attention for most of the fourth century A.D. Some have wondered, “Could anything be more foolish than arguing over a single letter in a word?” But the difference between the two words was profound, and the presence or absence of the iota really did mark the difference between biblical Christianity, with a true doctrine of the Trinity, and a heresy that did not accept the full deity of Christ and therefore was nontrinitarian and ultimately destructive to the whole Christian faith.

b. Subordinationism: In affirming that the Son was of the same nature as the Father, the early church also excluded a related false doctrine, subordinationism. While Arianism held that the Son was created and was not divine, subordinationism held that the Son was eternal (not created) and divine, but still not equal to the Father in being or attributes—the Son was inferior or “subordinate” in being to God the Father.27 The early church father Origen (c. 185-c. A.D. 254) advocated a form of subordinationism by holding that the Son was inferior to the Father in being, and that the Son eternally derives his being from the Father. Origen was attempting to protect the distinction of persons and was writing before the doctrine of the Trinity was clearly formulated in the church. The rest of the church did not follow him but clearly rejected his teaching at the Council of Nicea.

Although many early church leaders contributed to the gradual formulation of a correct doctrine of the Trinity, the most influential by far was Athanasius. He was only twenty-nine years old when he came to the Council of Nicea in A.D. 325, not as an official member but as secretary to Alexander, the Bishop of Alexandria. Yet his keen mind and writing ability allowed him to have an important influence on the outcome of the Council, and he himself became Bishop of Alexandria in 328. Though the Arians had been condemned at Nicea, they refused to stop teaching their views and used their considerable political power throughout the church to prolong the controversy for most of the rest of the fourth century. Athanasius became the focal point of Arian attack, and he devoted his entire life to writing and teaching against the Arian heresy. “He was hounded through five exiles embracing seventeen years of flight and hiding,” but, by his untiring efforts, “almost single-handedly Athanasius saved the Church from pagan intellectualism.”28 The “Athanasian Creed” which bears his name is not today thought to stem from Athanasius himself, but it is a very clear affirmation of trinitarian doctrine that gained increasing use in the church from about A.D. 400 onward and is still used in Protestant and Catholic churches today. (See appendix 1.)

c. Adoptionism: Before we leave the discussion of Arianism, one related false teaching needs to be mentioned. “Adoptionism” is the view that Jesus lived as an ordinary man until his baptism, but then God “adopted” Jesus as his “Son” and conferred on him supernatural powers. Adoptionists would not hold that Christ existed before he was born as a man; therefore, they would not think of Christ as eternal, nor would they think of him as the exalted, supernatural being created by God that the Arians held him to be. Even after Jesus’ “adoption” as the “Son” of God, they would not think of him as divine in nature, but only as an exalted man whom God called his “Son” in a unique sense.

Adoptionism never gained the force of a movement in the way Arianism did, but there were people who held adoptionist views from time to time in the early church, though their views were never accepted as orthodox. Many modern people who think of Jesus as a great man and someone especially empowered by God, but not really divine, would fall into the adoptionist category. We have placed it here in relation to Arianism because it, too, denies the deity of the Son (and, similarly, the deity of the Holy Spirit)

The controversy over Arianism was drawn to a close by the Council of Constantinople in A.D. 381. This council reaffirmed the Nicene statements and added a statement on the deity of the Holy Spirit, which had come under attack in the period since Nicea. After the phrase, “And in the Holy Spirit,” Constantinople added, “the Lord and Giver of Life; who proceeds from the Father; who with the Father and the Son together is worshipped and glorified; who spake by the Prophets.” The version of the creed that includes the additions at Constantinople is what is commonly known as the Nicene Creed today (See p. 1169 for the text of the Nicene Creed.)

d. The Filioque Clause: In connection with the Nicene Creed, one unfortunate chapter in the history of the church should be briefly noted, namely the controversy over the insertion of the filioque clause into the Nicene Creed, an insertion that eventually led to the split between western (Roman Catholic) Christianity and eastern Christianity (consisting today of various branches of eastern orthodox Christianity, such as the Greek Orthodox Church, the Russian Orthodox Church, etc.) in A.D. 1054.

The word filioque is a Latin term that means “and from the Son.” It was not included in the Nicene Creed in either the first version of A.D. 325 or the second version of A.D. 381. Those versions simply said that the Holy Spirit “proceeds from the Father.” But in A.D. 589, at a regional church council in Toledo (in what is now Spain), the phrase “and the Son” was added, so that the creed then said that the Holy Spirit “proceeds from the Father and the Son (filioque).” In the light of John 15:26 and 16:7, where Jesus said that he would send the Holy Spirit into the world, it seems there could be no objection to such a statement if it referred to the Holy Spirit proceeding from the Father and the Son at a point in time (particularly at Pentecost). But this was a statement about the nature of the Trinity, and the phrase was understood to speak of the eternal relationship between the Holy Spirit and the Son, something Scripture never explicitly discusses.29 The form of the Nicene Creed that had this additional phrase gradually gained in general use and received an official endorsement in A.D. 1017. The entire controversy was complicated by ecclesiastical politics and struggles for power, and this apparently very insignificant doctrinal point was the main doctrinal issue in the split between eastern and western Christianity in A.D. 1054. (The underlying political issue, however, was the relation of the Eastern church to the authority of the Pope.) The doctrinal controversy and the split between the two branches of Christianity have not been resolved to this day

Is there a correct position on this question? The weight of evidence (slim though it is) seems clearly to favor the western church. In spite of the fact that John 15:26 says that the Spirit of truth “proceeds from the Father,” this does not deny that he proceeds also from the Son (just as John 14:26 says that the Father will send the Holy Spirit, but John 16:7 says that the Son will send the Holy Spirit). In fact, in the same sentence in John 15:26 Jesus speaks of the Holy Spirit as one “whom I shall send to you from the Father.” And if the Son together with the Father sends the Spirit into the world, by analogy it would seem appropriate to say that this reflects eternal ordering of their relationships. This is not something that we can clearly insist on based on any specific verse, but much of our understanding of the eternal relationships among the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit comes by analogy from what Scripture tells us about the way they relate to the creation in time. Moreover, the eastern formulation runs the danger of suggesting an unnatural distance between the Son and the Holy Spirit, leading to the possibility that even in personal worship an emphasis on more mystical, Spirit-inspired experience might be pursued to the neglect of an accompanying rationally understandable adoration of Christ as Lord. Nevertheless, the controversy was ultimately over such an obscure point of doctrine (essentially, the relationship between the Son and Spirit before creation) that it certainly did not warrant division in the church.

e. The Importance of the Doctrine of the Trinity: Why was the church so concerned about the doctrine of the Trinity? Is it really essential to hold to the full deity of the Son and the Holy Spirit? Yes it is, for this teaching has implications for the very heart of the Christian faith. First, the atonement is at stake. If Jesus is merely a created being, and not fully God, then it is hard to see how he, a creature, could bear the full wrath of God against all of our sins. Could any creature, no matter how great, really save us? Second, justification by faith alone is threatened if we deny the full deity of the Son. (This is seen today in the teaching of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who do not believe in justification by faith alone.) If Jesus is not fully God, we would rightly doubt whether we can really trust him to save us completely. Could we really depend on any creature fully for our salvation? Third, if Jesus is not infinite God, should we pray to him or worship him? Who but an infinite, omniscient God could hear and respond to all the prayers of all God’s people? And who but God himself is worthy of worship? Indeed, if Jesus is merely a creature, no matter how great, it would be idolatry to worship him—yet the New Testament commands us to do so (Phil. 2:9–11; Rev. 5:12–14). Fourth, if someone teaches that Christ was a created being but nonetheless one who saved us, then this teaching wrongly begins to attribute credit for salvation to a creature and not to God himself. But this wrongfully exalts the creature rather than the Creator, something Scripture never allows us to do. Fifth, the independence and personal nature of God are at stake: If there is no Trinity, then there were no interpersonal relationships within the being of God before creation, and, without personal relationships, it is difficult to see how God could be genuinely personal or be without the need for a creation to relate to. Sixth, the unity of the universe is at stake: If there is not perfect plurality and perfect unity in God himself, then we have no basis for thinking there can be any ultimate unity among the diverse elements of the universe either. Clearly, in the doctrine of the Trinity, the heart of the Christian faith is at stake. Herman Bavinck says that “Athanasius understood better than any of his contemporaries that Christianity stands or falls with the confession of the deity of Christ and of the Trinity.”30 He adds, “In the confession of the Trinity throbs the heart of the Christian religion: every error results from, or upon deeper reflection may be traced to, a wrong view of this doctrine.”31

3. Tritheism Denies That There Is Only One God. A final possible way to attempt an easy reconciliation of the biblical teaching about the Trinity would be to deny that there is only one God. The result is to say that God is three persons and each person is fully God. Therefore, there are three Gods. Technically this view would be called “tritheism.”

Few persons have held this view in the history of the church. It has similarities to many ancient pagan religions that held to a multiplicity of gods. This view would result in confusion in the minds of believers. There would be no absolute worship or loyalty or devotion to one true God. We would wonder to which God we should give our ultimate allegiance. And, at a deeper level, this view would destroy any sense of ultimate unity in the universe: even in the very being of God there would be plurality but no unity

Although no modern groups advocate tritheism, perhaps many evangelicals today unintentionally tend toward tritheistic views of the Trinity, recognizing the distinct personhood of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, but seldom being aware of the unity of God as one undivided being.

D. What Are the Distinctions Between the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit?

After completing this survey of errors concerning the Trinity, we may now go on to ask if anything more can be said about the distinctions between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. If we say that each member of the Trinity is fully God, and that each person fully shares in all the attributes of God, then is there any difference at all among the persons? We cannot say, for example, that the Father is more powerful or wiser than the Son, or that the Father and Son are wiser than the Holy Spirit, or that the Father existed before the Son and Holy Spirit existed, for to say anything like that would be to deny the full deity of all three members of the Trinity. But what then are the distinctions between the persons?

1. The Persons of the Trinity Have Different Primary Functions in Relating to the World. When Scripture discusses the way in which God relates to the world, both in creation and in redemption, the persons of the Trinity are said to have different functions or primary activities. Sometimes this has been called the “economy of the Trinity,” using economy in an old sense meaning “ordering of activities.” (In this sense, people used to speak of the “economy of a household” or “home economics,” meaning not just the financial affairs of a household, but all of the “ordering of activities” within the household.) The “economy of the Trinity” means the different ways the three persons act as they relate to the world and (as we shall see in the next section) to each other for all eternity

We see these different functions in the work of creation. God the Father spoke the creative words to bring the universe into being. But it was God the Son, the eternal Word of God, who carried out these creative decrees. “All things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made” (John 1:3). Moreover, “in him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or principalities or authorities—all things were created through him and for him” (Col. 1:16; see also Ps. 33:6, 9; 1 Cor. 8:6; Heb. 1:2). The Holy Spirit was active as well in a different way, in “moving” or “hovering” over the face of the waters (Gen. 1:2), apparently sustaining and manifesting God’s immediate presence in his creation (cf. Ps. 33:6, where “breath” should perhaps be translated “Spirit”; see also Ps. 139:7)

In the work of redemption there are also distinct functions. God the Father planned redemption and sent his Son into the world (John 3:16; Gal. 4:4; Eph. 1:9–10). The Son obeyed the Father and accomplished redemption for us (John 6:38; Heb. 10:5–7; et al.). God the Father did not come and die for our sins, nor did God the Holy Spirit. That was the particular work of the Son. Then, after Jesus ascended back into heaven, the Holy Spirit was sent by the Father and the Son to apply redemption to us. Jesus speaks of “the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name” (John 14:26), but also says that he himself will send the Holy Spirit, for he says, “If I go, I will send him to you” (John 16:7), and he speaks of a time “when the Counselor comes, whom I shall send to you from the Father, even the Spirit of truth” (John 15:26). It is especially the role of the Holy Spirit to give us regeneration or new spiritual life (John 3:5–8), to sanctify us (Rom. 8:13; 15:16; 1 Peter 1:2), and to empower us for service (Acts 1:8; 1 Cor. 12:7–11). In general, the work of the Holy Spirit seems to be to bring to completion the work that has been planned by God the Father and begun by God the Son. (See chapter 30, on the work of the Holy Spirit.

So we may say that the role of the Father in creation and redemption has been to plan and direct and send the Son and Holy Spirit. This is not surprising, for it shows that the Father and the Son relate to one another as a father and son relate to one another in a human family: the father directs and has authority over the son, and the son obeys and is responsive to the directions of the father. The Holy Spirit is obedient to the directives of both the Father and the Son.

Thus, while the persons of the Trinity are equal in all their attributes, they nonetheless differ in their relationships to the creation. The Son and Holy Spirit are equal in deity to God the Father, but they are subordinate in their roles.

Moreover, these differences in role are not temporary but will last forever: Paul tells us that even after the final judgment, when the “last enemy,” that is, death, is destroyed and when all things are put under Christ’s feet, “then the Son himself will also be subjected to him who put all things under him, that God may be everything to every one” (1 Cor. 15:28).

2. The Persons of the Trinity Eternally Existed as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. But why do the persons of the Trinity take these different roles in relating to creation? Was it accidental or arbitrary? Could God the Father have come instead of God the Son to die for our sins? Could the Holy Spirit have sent God the Father to die for our sins, and then sent God the Son to apply redemption to us

No, it does not seem that these things could have happened, for the role of commanding, directing, and sending is appropriate to the position of the Father, after whom all human fatherhood is patterned (Eph. 3:14–15). And the role of obeying, going as the Father sends, and revealing God to us is appropriate to the role of the Son, who is also called the Word of God (cf. John 1:1–5, 14, 18; 17:4; Phil. 2:5–11). These roles could not have been reversed or the Father would have ceased to be the Father and the Son would have ceased to be the Son. And by analogy from that relationship, we may conclude that the role of the Holy Spirit is similarly one that was appropriate to the relationship he had with the Father and the Son before the world was created

Second, before the Son came to earth, and even before the world was created, for all eternity the Father has been the Father, the Son has been the Son, and the Holy Spirit has been the Holy Spirit. These relationships are eternal, not something that occurred only in time. We may conclude this first from the unchangeableness of God (see chapter 11): if God now exists as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, then he has always existed as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. We may also conclude that the relationships are eternal from other verses in Scripture that speak of the relationships the members of the Trinity had to one another before the creation of the world. For instance, when Scripture speaks of God’s work of election (see chapter 32) before the creation of the world, it speaks of the Father choosing us “in” the Son: “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ … he chose us in him before the foundation of the world that we should be holy and blameless before him” (Eph. 1:3–4). The initiatory act of choosing is attributed to God the Father, who regards us as united to Christ or “in Christ” before we ever existed. Similarly, of God the Father, it is said that “those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son” (Rom. 8:29). We also read of the “foreknowledge of God the Father” in distinction from particular functions of the other two members of the Trinity (1 Peter 1:2 NASB; cf. 1:20).32 Even the fact that the Father “gave his only Son” (John 3:16) and “sent the Son into the world” (John 3:17) indicate that there was a Father-Son relationship before Christ came into the world. The Son did not become the Son when the Father sent him into the world. Rather, the great love of God is shown in the fact that the one who was always Father gave the one who was always his only Son: “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son …” (John 3:16). “But when the time had fully come, God sent forth his Son” (Gal. 4:4)

When Scripture speaks of creation, once again it speaks of the Father creating through the Son, indicating a relationship prior to when creation began (see John 1:3; 1 Cor. 8:6; Heb. 1:2; also Prov. 8:22–31). But nowhere does it say that the Son or Holy Spirit created through the Father. These passages again imply that there was a relationship of Father (as originator) and Son (as active agent) before creation, and that this relationship made it appropriate for the different persons of the Trinity to fulfill the roles they actually did fulfill

Therefore, the different functions that we see the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit performing are simply outworkings of an eternal relationship between the three persons, one that has always existed and will exist for eternity. God has always existed as three distinct persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. These distinctions are essential to the very nature of God himself, and they could not be otherwise

Finally, it may be said that there are no differences in deity, attributes, or essential nature between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Each person is fully God and has all the attributes of God. The only distinctions between the members of the Trinity are in the ways they relate to each other and to the creation. In those relationships they carry out roles that are appropriate to each person

This truth about the Trinity has sometimes been summarized in the phrase “ontological equality but economic subordination,” where the word ontological means “being.”33 Another way of expressing this more simply would be to say “equal in being but subordinate in role.” Both parts of this phrase are necessary to a true doctrine of the Trinity: If we do not have ontological equality, not all the persons are fully God. But if we do not have economic subordination,34 then there is no inherent difference in the way the three persons relate to one another, and consequently we do not have the three distinct persons existing as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit for all eternity. For example, if the Son is not eternally subordinate to the Father in role, then the Father is not eternally “Father” and the Son is not eternally “Son.” This would mean that the Trinity has not eternally existed

This is why the idea of eternal equality in being but subordination in role has been essential to the church’s doctrine of the Trinity since it was first affirmed in the Nicene Creed, which said that the Son was “begotten of the Father before all ages” and that the Holy Spirit “proceeds from the Father and the Son.” Surprisingly, some recent evangelical writings have denied an eternal subordination in role among the members of the Trinity,35 but it has clearly been part of the church’s doctrine of the Trinity (in Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox expressions), at least since Nicea (A.D. 325). So Charles Hodge says:

The Nicene doctrine includes, (1) the principle of the subordination of the Son to the Father, and of the Spirit to the Father and the Son. But this subordination does not imply inferiority … The subordination intended is only that which concerns the mode of subsistence and operation …

The creeds are nothing more than a well-ordered arrangement of the facts of Scripture which concern the doctrine of the Trinity. They assert the distinct personality of the Father, Son, and Spirit … and their consequent perfect equality; and the subordination of the Son to the Father, and of the Spirit to the Father and the Son, as to the mode of subsistence and operation. These are scriptural facts, to which the creeds in question add nothing; and it is in this sense they have been accepted by the Church universal.36

Similarly, A.H. Strong says:

Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, while equal in essence and dignity, stand to each other in an order of personality, office, and operation …

The subordination of the person of the Son to the person of the Father, or in other words an order of personality, office, and operation which permits the Father to be officially first, the Son second, and the Spirit third, is perfectly consistent with equality. Priority is not necessarily superiority … We frankly recognize an eternal subordination of Christ to the Father but we maintain at the same time that this subordination is a subordination of order, office, and operation, not a subordination of essence.37

3. What Is the Relationship Between the Three Persons and the Being of God? After the preceding discussion, the question that remains unresolved is, What is the difference between “person” and “being” in this discussion? How can we say that God is one undivided being, yet that in this one being there are three persons?

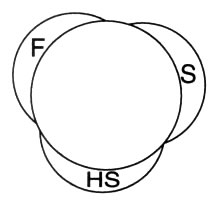

First, it is important to affirm that each person is completely and fully God; that is, that each person has the whole fullness of God’s being in himself. The Son is not partly God or just one-third of God, but the Son is wholly and fully God, and so is the Father and the Holy Spirit. Thus, it would not be right to think of the Trinity according to figure 14.1, with each person representing only one-third of God’s being.

Figure 14.1: God’s Being Is Not Divided Into Three Equal Parts Belonging to the Three Members of the Trinity

Rather, we must say that the person of the Father possesses the whole being of God in himself. Similarly, the Son possesses the whole being of God in himself, and the Holy Spirit possesses the whole being of God in himself. When we speak of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit together we are not speaking of any greater being than when we speak of the Father alone, or the Son alone, or the Holy Spirit alone. The Father is all of God’s being. The Son also is all of God’s being. And the Holy Spirit is all of God’s being.

This is what the Athanasian Creed affirmed in the following sentences:

And the Catholic Faith is this: That we worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; Neither confounding the Persons: nor dividing the Substance [Essence]. For there is one Person of the Father: another of the Son: and another of the Holy Spirit. But the Godhead of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, is all one: the Glory equal, the Majesty coeternal. Such as the Father is: such is the Son: and such is the Holy Spirit … For like as we are compelled by the Christian verity: to acknowledge every Person by himself to be God and Lord: So are we forbidden by the Catholic Religion: to say, There be [are] three Gods, or three Lords.

But if each person is fully God and has all of God’s being, then we also should not think that the personal distinctions are any kind of additional attributes added on to the being of God, something after the pattern of figure 14.2.

Figure 14.2: The Personal Distinctions in the Trinity Are Not Something Added Onto God’s Real Being

Rather, each person of the Trinity has all of the attributes of God, and no one person has any attributes that are not possessed by the others.

On the other hand, we must say that the persons are real, that they are not just different ways of looking at the one being of God. (This would be modalism or Sabellianism, as discussed above.) So figure 14.3 would not be appropriate.

Figure 14.3: The Persons of the Trinity Are Not Just Three Different Ways of Looking at the One Being of God

Figure 14.3: The Persons of the Trinity Are Not Just Three Different Ways of Looking at the One Being of God

Rather, we need to think of the Trinity in such a way that the reality of the three persons is maintained, and each person is seen as relating to the others as an “I” (a first person) and a “you” (a second person) and a “he” (a third person).

The only way it seems possible to do this is to say that the distinction between the persons is not a difference in “being” but a difference in “relationships.” This is something far removed from our human experience, where every different human “person” is a different being as well. Somehow God’s being is so much greater than ours that within his one undivided being there can be an unfolding into interpersonal relationships, so that there can be three distinct persons.

What then are the differences between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit? There is no difference in attributes at all. The only difference between them is the way they relate to each other and to the creation. The unique quality of the Father is the way he relates as Father to the Son and Holy Spirit. The unique quality of the Son is the way he relates as Son. And the unique quality of the Holy Spirit is the way he relates as Spirit.3

While the three diagrams given above represented erroneous ideas to be avoided, the following diagram may be helpful in thinking about the existence of three persons in the one undivided being of God.

Figure 14.4: There Are Three Distinct Persons, and the Being of Each Person Is Equal to the Whole Being of God

In this diagram, the Father is represented as the section of the circle designated by F, and also the rest of the circle, moving around clockwise from the letter F; the Son is represented as the section of the circle designated by S, and also the rest of the circle, moving around clockwise from the letter S; and the Holy Spirit is represented as the section of the circle marked HS and also the rest of the circle, moving around clockwise from the HS. Thus, there are three distinct persons, but each person is fully and wholly God. Of course the representation is imperfect, for it cannot represent God’s infinity, or personality, or indeed any of his attributes. It also requires looking at the circle in more than one way in order to understand it: the dotted lines must be understood to indicate personal relationship, not any division in the one being of God. Thus, the circle itself represents God’s being while the dotted lines represent a form of personal existence other than a difference in being. But the diagram may nonetheless help guard against some misunderstanding